Fever? Burning eyes? Back and neck pain?

If you had those ailments while living in Houston 139 years ago, you were in trouble.

September 1867 was a particularly nasty time as the town was hit with a

yellow fever epidemic. This wasn’t the first time “yellow jack” or the “black vomit” made an appearance. In 1858,

175 Houstonians died of the disease (about 3.6 percent of Houston’s population at the time). The following year, 15 to 24 people were dying at its peak. Before then, yellow fever and cholera killed so many people in such a short amount of time that bodies were dumped into long trenches at the old city cemetery (on West Dallas) and covered without a funeral ceremony.

But in the midst of the 1867 outbreak, the alarm raised by the Houston Daily Telegraph was mitigated by reports that few were dying of the disease.

“The number of cases will doubtless exceed 700. The mortality when we consider the number of cases, is very light,” the newspaper reported on Sept. 15, 1867.

From Aug. 12 to Sept. 14, 105 people had already died of yellow fever. In all, 492 would die by the time the outbreak subsided.

(That number is nearly 6 percent of the town's population. In 1860, Houston had a population of 4,845, according to Census figures. Ten years later, the town had a population of 9,382. For this calculation, the population of Houston at 1867 was estimated at 8,700. To put that in perspective, Houston's population in 2005 was estimated at 2,016,582. Six percent of that is 120,994. It makes one wonder how people today would react if that many residents of one city were to die of a particular disease in the span of a few months. Math experts are more than welcome to correct me!)

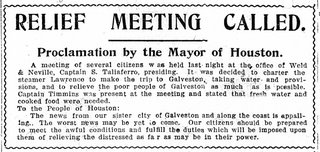

Galveston took a harder hit as more that 720 people died there by early September, according to the Handbook of Texas.

Among the dead:

Dick Dowling

Dick Dowling – Born in Ireland, settled in Houston and became a successful businessman. Among his businesses were Shades (a saloon) and the Bank of Bacchus near the Harris County courthouse. He fought for the Confederacy at the

Battle of Galveston and played a key role in its victory at the

Battle of Sabine Pass. A statue erected in 1905 that once stood on the site of the old City Hall at Market Square now stands at the entrance of Hermann Park on North MacGregor.

J.F. Wallace – Harris County assessor and collector

M. Bawsell – Deputy postmaster

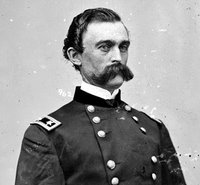

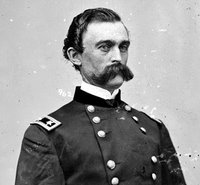

General Charles Griffin – Born in Ohio, Griffin graduated from West Point in 1847. He went on

to fight in the Mexican-American War and led Union troops during the Civil War battles at Antietam and Bull Run. He was present when Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House.

In Texas, Griffin took command of the

Freedmen’s Bureau and military district of Texas during Reconstruction. During that time, he became heavily involved in Reconstruction politics.

But as yellow fever began to take hold of Galveston, he was urged to move his headquarters to Houston and establish a military quarantine, the Houston Daily Telegraph reported.

“But, with the true spirit of a soldier, he refused, saying that he was at his post and there he intended to remain,” according to the paper.

Yellow fever claimed his only son during the epidemic. By mid-September, Griffin also was dead.

“All who visited him, whatever differences of opinion might exist between them, came away pleased with him. … He was a stranger among the people of Texas, had fought against them in the war and was their military ruler at the time of his death. … Nevertheless, they feel sad at his untimely death and deeply sympathize with his excellent lady,” the Daily Telegraph reported on Sept. 17.

Labels: disasters

she demanded the film be removed from exhibition.

she demanded the film be removed from exhibition.

Dick Dowling

Dick Dowling