Houston History Mystery V: The case of the missing portrait

It’s Halloween, which gives me a good excuse to post this photoshopped picture I took of the old Jefferson Davis Hospital years ago.

It’s Halloween, which gives me a good excuse to post this photoshopped picture I took of the old Jefferson Davis Hospital years ago.Speaking of JDH, here’s another Houston History Mystery that needs solving.

On Dec. 2, 1924, members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy met with hospital, city and county officials to officially open the hospital.

On Dec. 2, 1924, members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy met with hospital, city and county officials to officially open the hospital.It’s no coincidence that local leaders scheduled the hospital’s dedication ceremony at the same time UDC members were meeting in Houston.

The high point of the ceremony was the unveiling of a portrait of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. The UDC presented the portrait to hospital officials.

Judge Sam Streetman, president of the local hospital board, hoped the portrait would “stand as a constant reminder of the highest conception of honor and duty as expressed in the life of Jefferson Davis.”

A bronze tablet commemorating the Confederate veterans was to have been presented at the ceremony, too, but it was not ready.

Obviously, the tablet and the portrait were removed at some point. No one seems to know where the items are located. I seem to remember contacting the UDC about it years ago, but no one knew anything about it. With the current inclination to remove all things related to the Confederacy, it’s easy to believe that both the painting and tablet have been lost for good.

Labels: Houston History Mystery

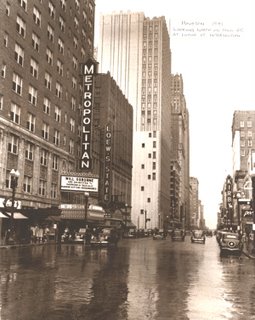

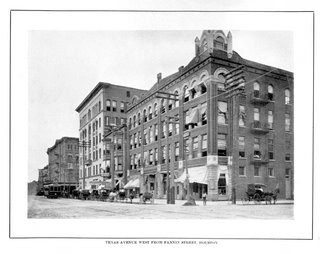

And for the Galveston folks...Market Street, 1907.

And for the Galveston folks...Market Street, 1907.